LeanVisual Management

- 10 minute read

Learn how enterprises create a more efficient workplace and boost Lean transformation initiatives by optimizing digital collaborative meeting rituals.

It’s a fact that organizations can’t improve unless they constantly seek out and solve their problems. For most, this requires a profound cultural change, which must start at the top.

The following phenomenon can be observed: When a company involves its employees in problem-solving daily, they feel more motivated, do their jobs better, the organization’s performance improves, and a virtuous circle is set in motion.

In this article, we’ll look at 5 best practices for establishing a lasting problem-solving culture!Large organizations have well-established routines for major projects: appointing a project manager, setting objectives and monitoring progress at regular intervals. If these important projects aren’t progressing in the right direction or at the right speed, management steps in. Indeed, managers themselves, having grown up in this type of environment, consider the implementation of these major strategic projects to be central to their work.

Yet focusing solely on these big projects is often a mistake. Small problems count too.

A concrete example: a well-designed application form and good file transmission between sales and underwriting can reduce rework and improve customer service.

Monitoring these issues requires constant effort and a systematic method of escalating them. The project-based approach used to manage large-scale interventions doesn’t work on this fragmented scale. However, Mckinsey explains that it has seen different systems in organizations to “solve” many small problems that the organization had not yet properly defined or understood.

If a project-based approach doesn’t work, what’s the solution?

In reality, the only way to deal with these little day-to-day problems is to detect and solve them as they arise (or even before).

This means that managers & executives move from the mindset of “I know the answers and direct the employees” to “I learn from the people who are closest to the problems and coach them”.

In effect, we’re moving to a model of solving hundreds of small problems every year – instead of just managing the big projects, which requires developing a more distributed problem-solving capability.

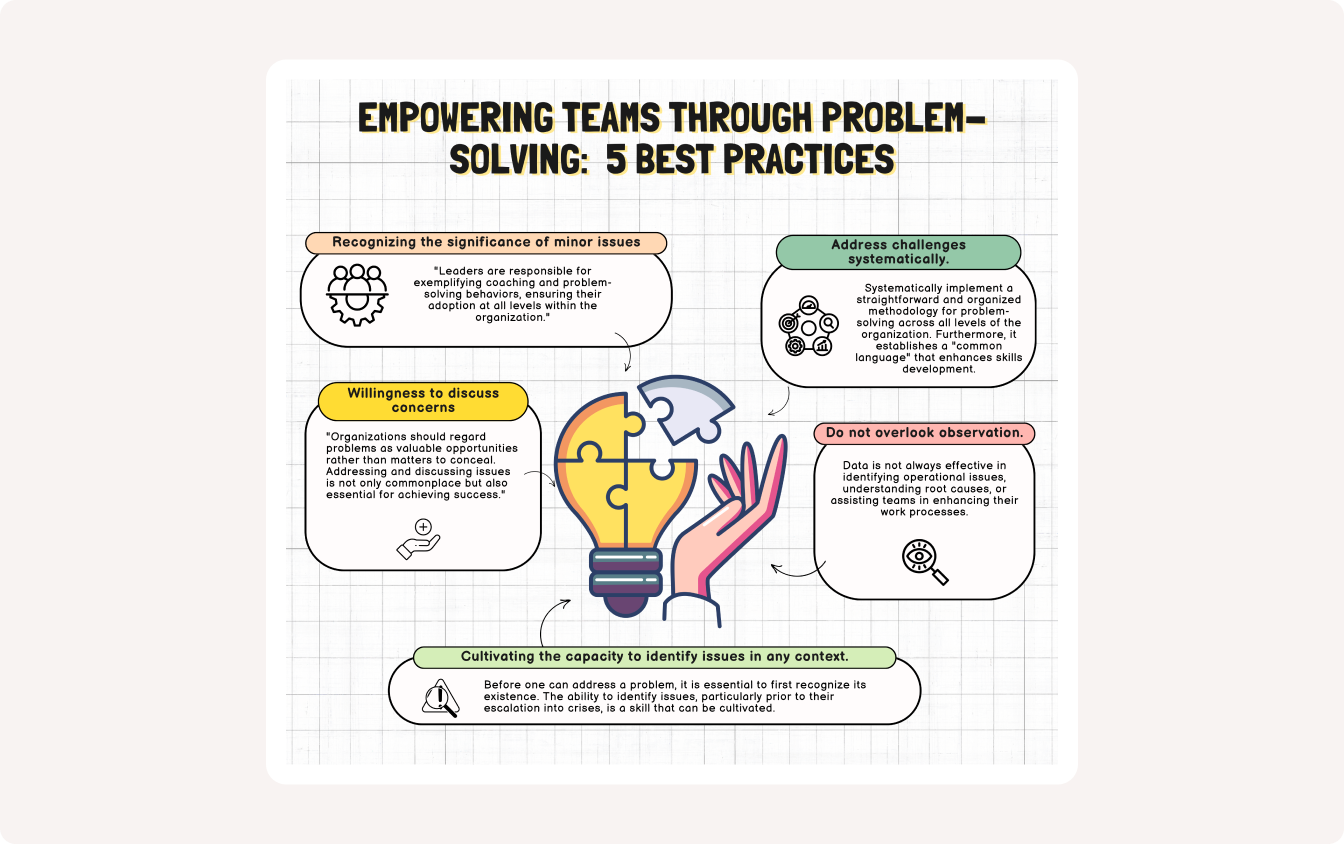

Leaders are responsible for modeling problem-solving coaching and analysis behaviors and ensuring they are adopted at all levels of the organization.

What to aim for: Everyone in the organization takes the initiative to solve the most relevant problems. This may take several years, but once it has taken root, the results are convincing.

First, it’s interesting to look at the vocabulary we choose when we talk about problems.

At first glance, talking about “challenges” or “opportunities” rather than “problems” may seem like a good way to avoid sounding negative. However, good problem-solving starts with the ability to recognize problems and see them without judgment.

The idea is this: If an organization treats problems as negative things (mistakes, flaws, or failures), it will become uncomfortable for people to expose them. However, problems that remain hidden will not be solved, and unresolved problems prevent the organization from achieving its objectives.

Reluctance to acknowledge problems often stems from the tendency to look for a culprit instead of a cause. This habit is hard to break, even for those who know how destructive it can be.

So what’s the right thing to do?

Neither assigning blame nor ignoring a problem is helpful. Organizations that embrace continuous improvement take the opposite approach. They understand that when the problem is correctly identified, the root cause usually turns out to be an underlying factor that the organization can correct, such as a lack of transparency, poor communication, inadequate training, or misaligned incentives.

Organizations need to see problems as something to be valued, not hidden. Raising and discussing problems is not only normal but desirable and essential to success.Before you can solve a problem, you must first be able to recognize it. Identifying problems, especially before they develop into crises, is an acquired skill.

In the lean philosophy, every problem can be linked to some form of waste, variability, or overload. Learning to detect these elements as soon as they appear is one of the key skills that managers and their organizations can cultivate. I recommend that you always remember the 7 forms of waste (7 MUDAS) when questioning: Overproduction – Overprocessing – Unnecessary stocks – Unnecessary transport – Unnecessary movements – Errors, insufficient quality – Waiting times.

Problems are often difficult to spot when they are integrated into the “usual way of doing things”. Some companies value practices that their top performers adopt to get around reluctant partners or inflexible IT processes. Yet closer examination shows that these practices deliver no value from the customer’s point of view.

Take the example of a logistics company where inventory managers have become accustomed to bypassing an outdated automatic tracking system. Rather than relying on real-time updates to track inventory flows, they preferred to manually check stock status by physically visiting warehouses. Over time, these managers became so proud of their “in-the-field” expertise that they saw this bypass skill as an asset. The company, not seeing the problem, even came to encourage this manual method, creating a dependency on physical checks and slowing down the adoption of a digital tracking system.Many managers pride themselves on their problem-solving skills. However, when it comes to their approach, they often tend to react instinctively rather than methodically.

Too often, they define the problem poorly, rely on intuition rather than facts, and jump to conclusions without stepping back to ask the right questions. They fall into the trap of confusing decision-making with problem-solving and rush to act instead of taking the time to reflect.

Why does this happen? Because following a rigorous process requires patience and discipline.

The aim is to systematically apply a simple, structured approach to problem-solving at all levels of the company can develop more than just rigor: it creates a “common language” that facilitates skills development and inter-departmental collaboration.

It’s important to keep the approach simple, without rushing into complex problem-solving techniques before having fully exploited the potential of simple methods.

What’s important: Identify the problems, Ask the right questions, Involve everyone in the search for solutions, and develop problem-solving skills within the organization.

My recommendation for effective problem-solving is to use the DMAIC method (Define, Measure, Analyze, Innovate, Control):

Taiichi Ohno, considered the “father” of lean manufacturing, used to say that, while data is useful, observed facts are essential.

When operational data is lacking, teams can gain valuable insights by simply observing their colleagues in action, and interviewing them to understand their working methods and motivations. Observation and interaction are key to revealing processes, workflows, constraints, and frustrations.

Take the example of a supply chain management team in a food distribution company. They notice that some products are reaching the shelves slightly late, leading to temporary stock-outs. Rather than spending time on an exhaustive analysis of shipping times, the team decides to observe the receiving and replenishment stages directly. Within a few days, they identify that some employees are taking longer to check the quality of products on pallets, creating delays for fast-moving products.

Many organizations excel at collecting and analyzing financial and accounting data for reporting purposes. Executives receive a constant stream of management information on revenues, costs, volumes, and so on. However, this data is oriented towards financial results and acts as a rear-view mirror, offering a retrospective view of past performance rather than helping to anticipate and improve the future. It can rarely be used to identify operational problems, understand their root causes, or help teams improve their work processes.